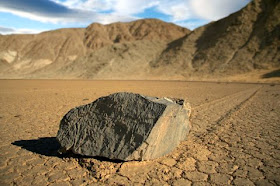

Santa Barbara Team Discovers Wind and Ice Behind the Racetrack’s “Sailing Stones”HOW THE HECK? A sailing stone leaves a trail after it scooted along The Racetrack. (Scott Beckner)

by Matt Kettmann

Santa Barbara Independent

In a landscape dominated by marvelous natural oddities, no location fascinates more visitors to Death Valley National Park than The Racetrack, a cracked-earth playa where rocks big and small magically move from place to place, leaving distinctly smooth tracks across the otherwise uniform lake bed as their only evidence. For decades, if not centuries, the phenomenon mystified even the most diligent researchers, becoming a standard passage in geology textbooks, prompting more than one dozen scientific inquiries, and provoking all manner of possible causes, from tricks by frat boys to the handiwork of little green men.

The mystery is no more, thanks to Santa Barbara native Jim Norris, who — along with his cousin, Richard Norris, and a team of mostly S.B.-based volunteers — discovered through a mix of amateur investigation and lucky happenstance exactly how these stones sail. In a paper published this week in the scholarly journal Plos One, Norris and company reveal how last winter — amid a very rare convergence of freezing temperatures and a standing playa pool of recent rain and snowmelt — they documented football-field-sized sheets of windowpane-thin ice being floated by wind across the slick, muddy playa and pushing the rocks, some as far as 700 feet.

“We watched it happen,” said Norris, who started monitoring Racetrack movements in 2012 as part of a “recreational science” experiment and was on-site for routine equipment maintenance in late December when the event occurred. “The sheets of ice start ramming into the stones and bulldozing them along. It’s all ultra-slow-motion.” The discovery, which has been sought scientifically since at least 1948, when the first academic paper was published about the rocks, is quickly making waves in the annals of popular science, with reports published this week in the Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, and Nature, among other publications.

Norris first visited The Racetrack in the 1960s with his father, the late Robert Norris, who was a professor of geology for many years at UCSB. The younger Norris, a graduate of Vieja Valley, San Marcos High, and San Diego State, became more intrigued in 2008, when he started scouring existing reports. He enlisted his cousin Richard, a paleobiologist at UC San Diego, in the completely self-financed hunt, and they set about equipping research-ready rocks with GPS tracking devices, which are one of the things that Norris makes for his engineering company, Interwoof. The first rocks were laid in early 2012 with National Park Service blessing, and the team made trips there every six to eight weeks.

In late November 2013, a brief rain and snowstorm formed a three-inch-deep pool on the playa, which was still there when the Norris cousins arrived in late December. Surprised by the pool and unable to enter the playa due to the “complete slop” of mud that sat on the surface, the cousins worked the northern part of the area and noticed that the pool seemed to be blowing uphill toward the playa’s mudflats as the winds increased. Soon, their rocks were actually moving for the first time.

“We started documenting it hard, not really understanding exactly what it meant,” said Norris, who determined what was happening over the next couple of days and subsequent trips, thanks to more observations and camera footage. “I think other people have probably been there when it happened, but they can’t tell,” said Norris. “It’s slow and so far away and at an oblique angle.”

The news throws a wrench into theories related to magic, magnetism, or Area 51. “I’ve even seen a wonderful photograph of a horned lizard pushing a stone,” said Norris, with a laugh. “It’s pretty amazing what the public will come up with.” But most in the scientific community figured the phenomenon was somehow reliant on ice and wind, so the Norrises had also erected a weather station as part of their project and were prepared to spend more than 10 years before reaching any conclusions. But despite the technology, had they not been on-site to witness the sheet ice bulldozers, the Norrises might still be scratching their heads, even with data in hand, especially since the movement occurred with relatively light wind rather than the hurricane force gales widely suspected.

Norris admits feeling “a little wistful” at having pulled the curtain off of Death Valley’s beloved mystery and knows there will be some public dismay. But he hopes it may shed light on processes elsewhere in the universe — important planetary scientists, for instance, have researched The Racetrack before — and he believes knowing is more important than supposing. He explained, “It’s hard to be a scientist, and I’m just an amateur scientist, and not want to figure stuff out and not get joy out of going, ‘Wow, that’s how this works!’”