Federal-lands ranching: A half-century of decline

How grazing fell from its Western pedestal — and fueled Sagebrush Rebellion.

Tay Wiles and Brooke Warren

High Country News

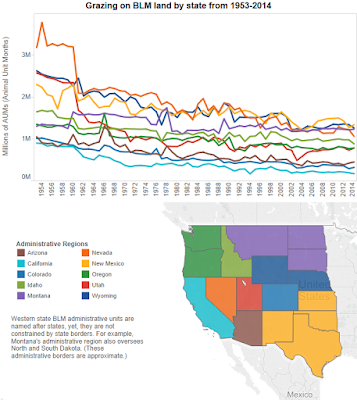

One of the prime drivers of the 45-year-old Sagebrush Rebellion, the movement to take control of public lands from the federal government, is the sense that rural Western ranchers are bullied by forces beyond their control. That narrative remains compelling, in part because it’s true. Since the 1950s, the ranching industry has been battered by market consolidation, rising operational costs, drought and climate change. Meanwhile, the amount of grazing allowed on federal lands has dramatically fallen. Bureau of Land Management livestock authorizations dropped from over 18 million animal unit months in 1953 to about 8 million in 2014.

Political rhetoric often blames the decline entirely on environmental regulation. But while the 1970s legislative changes have had an impact, there’s a more complex set of forces at work. The market for materials like lamb and wool fell after World War II, for example. Urban development became a factor as the feds sold off land to private buyers. Feedlots proliferated, squeezing smaller ranchers out of the market, and grazing fees rose. Then the advent of range science — which aims to use a coherent scientific method to determine how much grazing the land can sustain — changed everything.

Since then, drought has forced ranchers to sell off animals that their allotments can no longer support. What was then the costliest drought in the nation’s history hit Montana, Idaho and Wyoming particularly hard in the late 1980s, causing $39 billion in damages altogether. The 2002 dry spell, which sparked what was, at the time, one of the biggest fire seasons in Western history, pushed more cattle off the land. The current dry spell has also reduced livestock numbers, particularly in California and Nevada. The effects of drought can linger for years, as ranchers labor to restock, and replacement livestock from other regions struggle, sometimes unsuccessfully, to adapt to a new landscape. And once grazing levels are down, federal agencies historically have “made a habit of not letting them go back up,” says Leisl Carr-Childers, an American West and environmental historian.

BLM and USFS early stocking rates were difficult to measure accurately, as federal policies gave ranchers the incentive to report no more and no fewer animals than they were officially permitted. Read on for a look at 50 years of grazing data, from decades of U.S. Forest Service and BLM reports.

Notes on sourcing and methodology:

- This data originated from BLM and USFS annual reports.

- BLM and USFS early stocking rates were difficult to measure accurately, as federal policies gave ranchers the incentive to report no more and no fewer animals than they were officially permitted, which may have differed from actual cattle on the range.

- Agencies first measured “actually grazed” territory in the ’50s and ’60s by trudging onto rangelands and counting cattle; because of the method’s difficulty, they later began measuring based on billed AUMs.

- Before 1977, the Forest Service measured by animal-month, so those numbers have been converted to be consistent with animal-unit-month. We followed the agency’s recommendations and multiplied the early numbers by a factor of 1.2. However, this is not an exact conversion.

- The average weight of a cow has increased since the early 20th century, which means each AUM may have a potentially higher environmental impact.

- Forest Service data for 1992 and 1999 are unavailable.